Big tech can be quite secretive about the details of their operations.

Few break out their profits and losses by country, especially not for Australia.

Those of us who want to know what’s happening are stuck behind a veil of uncertainty.

But when the annual corporate tax transparency reports come out, the veil is briefly lifted and we get a flash of insight.

The report came out earlier his month and it’s absolutely fascinating.

How much income are they reporting (a proxy for revenue) and how much of that is turning into taxable income (a proxy for profit)?

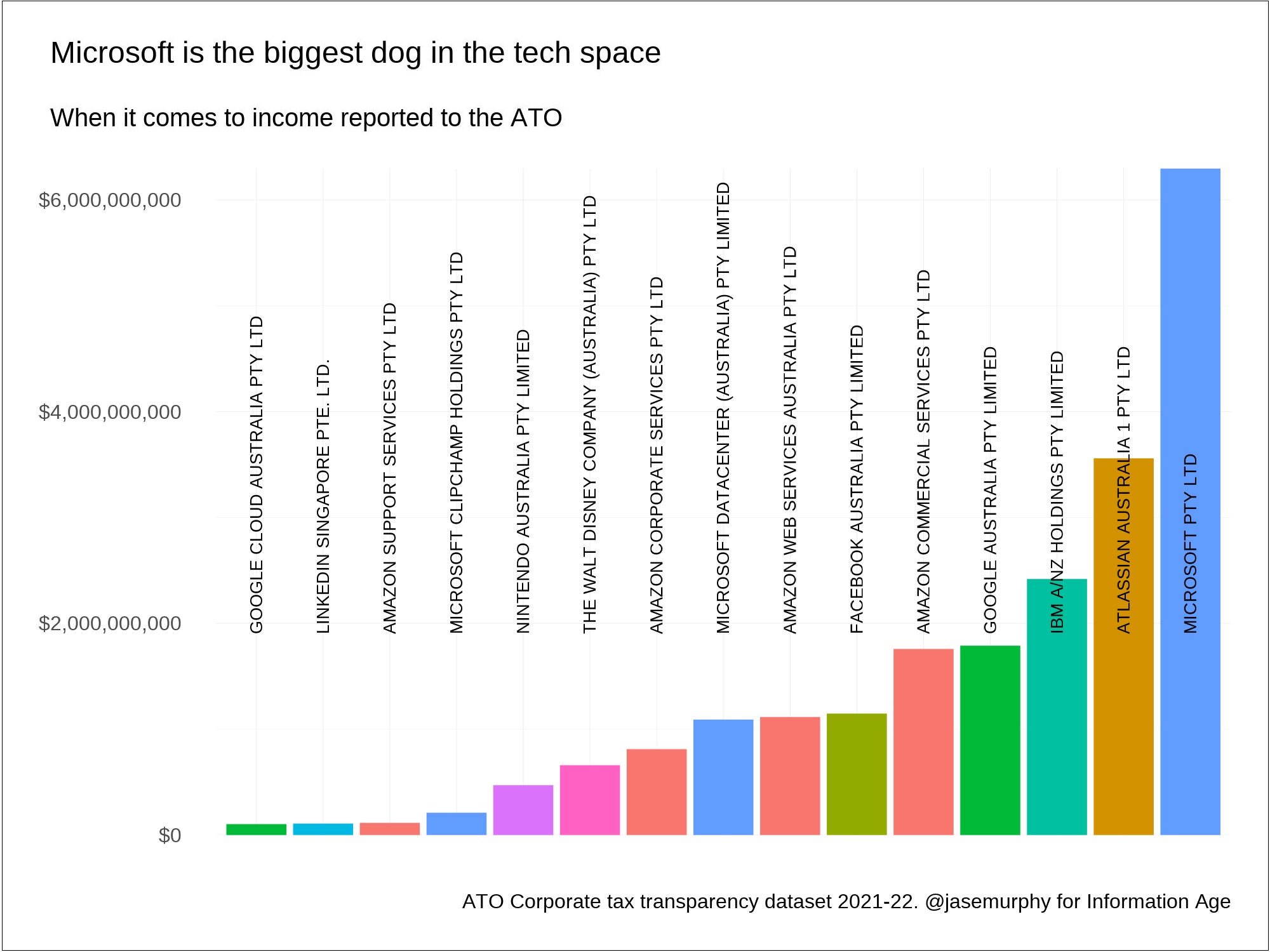

Let’s look at some massive names and see how much income they report in Australia.

The results may surprise you.

Amazon is one to watch here, since it has four entries on the chart (in red).

Combined, they are almost as big as Microsoft’s whopping revenue (three in blue, plus LinkedIn in turquoise).

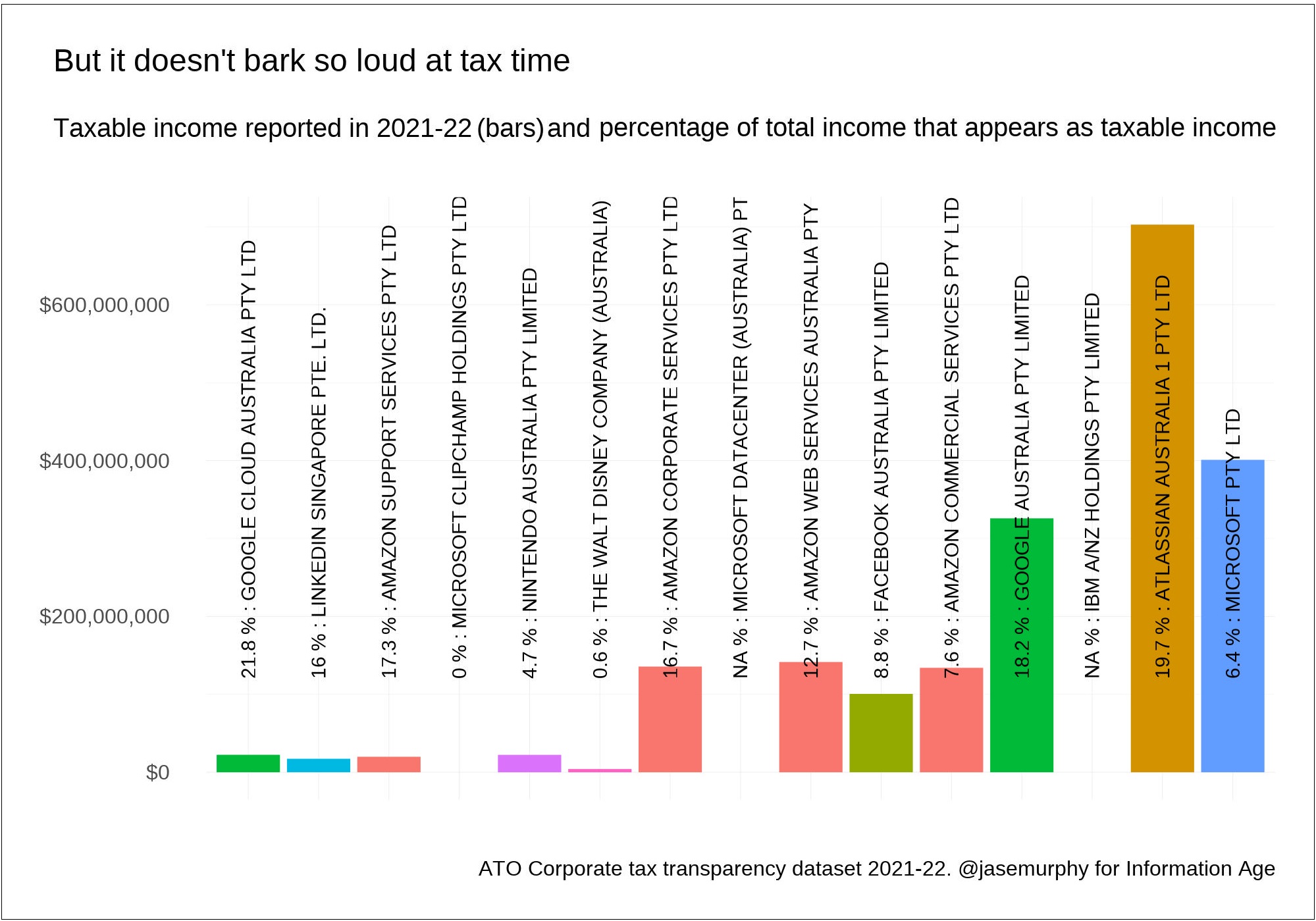

But when that turns to tax payable, the divergences are even more fascinating.

As you can see, Atlassian reports that a lot of their Australian income counts as taxable income: nearly 20%. (You only pay tax on your profits so taxable income is a proxy for profit).

Google Cloud also seems to have fat profit margins: it declares 21.8 per cent of total income as taxable income.

IBM and Microsoft’s local datacentre are the opposite, reporting no tax payable.

We expect companies with high profit margins to report a lot of taxable income relative to their income, and so we get a hint that Disney is not super profitable in Australia, or at least was not in 2021-22.

Of course, these numbers can be skewed in any one year by accounting anomalies like asset sales; asset write downs and other such things.

So, we should look at more than just one year to draw conclusions.

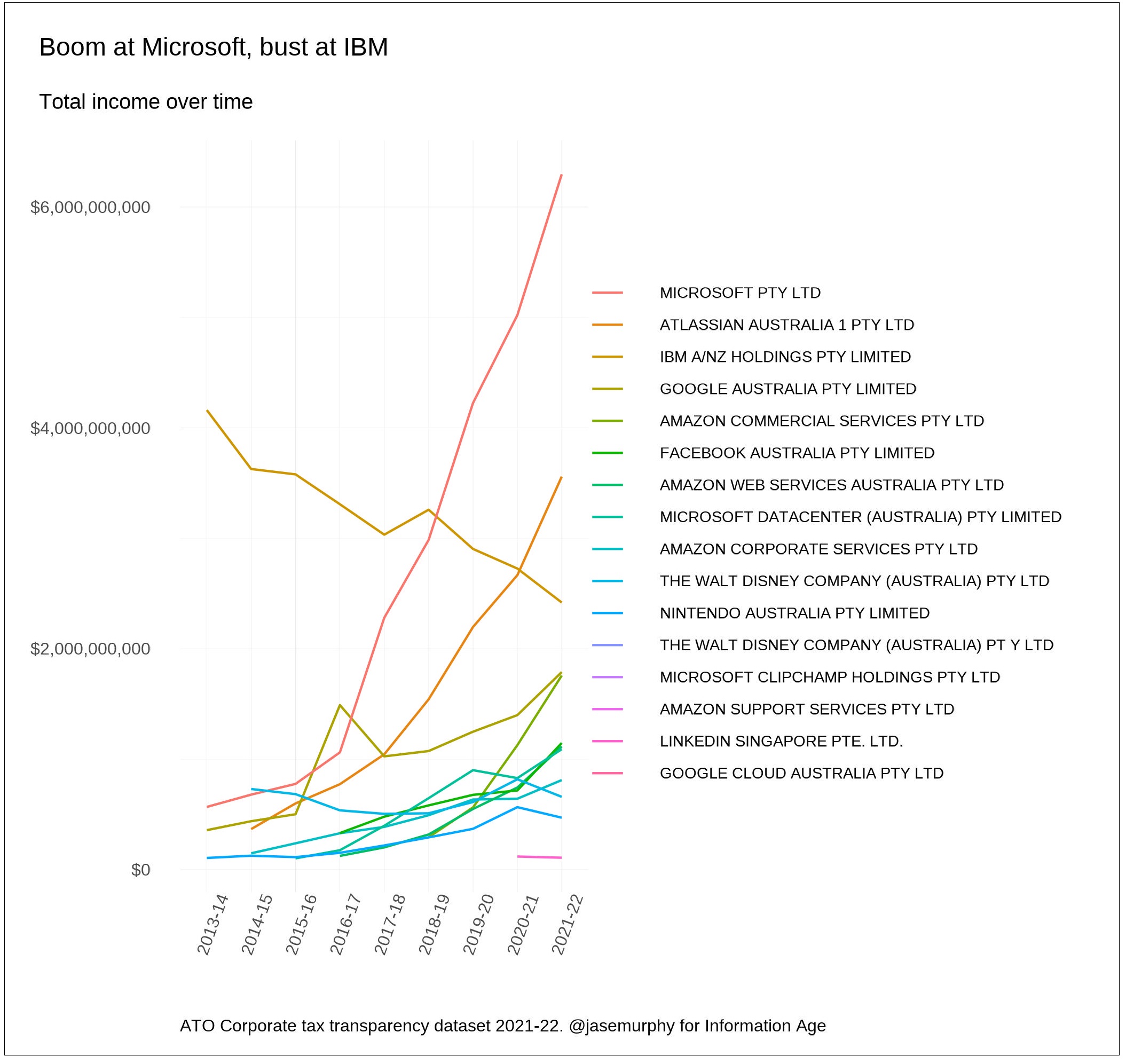

Here are the total income results in a time series; we see that Microsoft has grown revenues much more strongly than IBM.

Google’s total income is growing far more slowly and Amazon Commercial Services looks to be overtaking it.

The profit pachyderm

There’s also the elephant in the room.

Profit shifting.

When Microsoft sells copies of Windows in Australia, how do they calculate the Australian costs associated with that sale?

Is it pure profit? Or are there so many Aussie costs that the local profit is low?

This is a major focus of global tax law because companies like to create a situation where their costs are high in jurisdictions where they make a lot of sales, and transfer the profit back to places where the tax rate is low.

It’s fun to make zero profit in Australia where the tax rate is 30 per cent and billions in profit in Ireland where the company tax rate is 12.5 per cent.

The trick is to license your intellectual property.

You say the Irish address owns the right to the code and the brand names, and you make the Australian address pay license fees.

It’s a good trick because it’s hard to stop, hard to say the license fees are too high.

This article does not contend the companies in this story are doing anything illegal or even immoral.

The Centre for International Corporate Tax Accountability and Research has been less cautious.

The big tech companies are all publicly committed to obeying tax law.

But profit shifting certainly a topic that has been of interest when it comes to big tech.

The OECD says the digitalisation of the economy is the big threat to tax collections.

Several of these companies have addresses in Ireland so they can take advantage of its low tax rates.

And that’s basically an obligation they have to their shareholders – they are supposed to maximise profits, and they’d be mad, when choosing where to base their intellectual property, to put them somewhere where they end up paying high tax.

Microsoft has an address in the centre of Dublin, near the River Liffey.

Of course, they sell copies of Microsoft Excel and Xboxes In Ireland so they need a local address, but there’s a lot of assets registered there too.

Exactly how many? It’s hard to say.

The company has a special structure that reduces its need to report on its asset holdings under Irish law.

But as the OECD says, profit shifting tax avoidance can “cost countries 100-240 billion USD in lost revenue annually, which is the equivalent to 4-10% of the global corporate income tax revenue.”

Australia has been chasing tax from big multinational tax companies, but ultimately we can’t do it on our own.

Getting tax revenue from them requires global coordination.

And that is slow process that requires a lot of meetings.

The 2022-23 Budget included an announcement that the next phase of profit shifting rules would be implemented, including a 15 per cent minimum tax.

The government expects to increase tax receipts by $370 million over five years as a result.