A push towards decarbonisation is stronger than ever if Australia is to reduce its reliance on fossil fuels and achieve its emissions reduction target.

However, the race to achieve targets has brought several other issues.

Fossil fuels such as coal, oil and gas are by far the largest contributor to global climate change, accounting for over 75 per cent of global green house gas emissions.

To avoid worst impacts of climate change, emissions need to be reduced by almost half by 2030, and net zero by 2050.

Renewable energy technologies are leading the way and their sources are available and abundant, provided by the sun, wind, water and heat.

Many renewable innovations are already in use, from solar power, energy storage, electric vehicles to innovative heat pumps, hydrogen technologies, electricity grids and other alternatives for coal, oil and gas.

Technology advancements have lowered costs.

In 2017, CSIRO analysis estimated it would cost the country a trillion dollars to convert to renewable; today the current estimate is much lower at $500 billion.

While this appears to be good news, there are hidden costs that need to be addressed.

Environmental consultant, David Hines from Land and Water Management, Queensland says, the production process needs more consideration.

His concern is that some of the components are manufactured overseas in 'low cost countries'. In those countries, the production systems will almost all use fossil fuels.

“If we produce these solar panels in countries where policies are not as stringent, or fully enforced as here, the pollution impact is significant and, materials used are toxic from processing to dealing with waste.”

Studies have shown the heavy metals in solar panels namely lead and cadmium, can leach out of the cells and get into groundwater, as well as affect plants.

These metals also have a record for detrimental effects on human health. Lead is commonly known to impair brain development in children, and cadmium is a carcinogen.

In 2016, the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) estimated there were about 250,000 metric tonnes of solar panel waste in the world at the end of that year.

IRENA projected this amount [of solar panel waste] could reach 78 million metric tonnes by 2050.

Hines is advocating for more stringent assessments in countries producing renewable technology.

“We need to be sure that we are not exporting pollution overseas.

“The idea that solar panels, or electric cars, reduce the atmospheric carbon and are 'emissions free' is a case in point.

“When solar panels are installed en mass over land, they have been shown to leak toxic materials, with long term affects.”

To avoid poor decisions that will be felt decades later, Hines wants more tools developed to estimate the degree of significance of the impacts.

Adelaide University researcher, Michael McLaughlin has spent time studying the risks associated with cadmium from other agricultural sources like fertiliser and other solar products.

McLaughlin’s research includes the behaviour and toxicity of nutrients and contaminants in the soil-plant system, the assessment and remediation of contaminated soils, and use of advanced techniques to measure and monitor nutrients and pollutants in the environment.

Based on his study and overseas studies, McLaughlin said the risk of cadmium leaching from solar panels into the soil is low and that most landfill sites should be able to handle them.

“Most landfills have good leachate treatment and monitoring; it should be able to be managed if those systems are operating correctly."

The Challenge Ahead

Solar power is not going anywhere and it’s booming.

Global photovoltaic capacity grew from 1.4 GW in 2000 to 760 GW in 2020. Solar power now generates almost 4 per cent of the world’s electricity, according to the International Energy Agency.

Experts say this growth in low-carbon power is also a ticking time bomb.

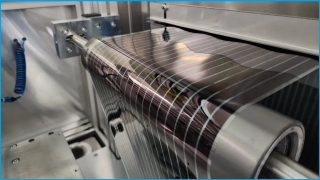

More than 90 per cent of photovoltaic (PV) panels rely on crystalline silicon and have a life span of about 30 years.

Forecasts suggest that 8 million metric tons of these panels will have reached the end of their working lives by 2030, a tally that is projected to reach 80 million by 2050.

Once they have reached the end of their lives, many of these dead panels are dumped in landfills, even though they contain valuable elements such as silicon, silver, and copper.

Researchers are now racing to develop chemical technologies that can help dismantle solar cells and strip away the valuable metals within.

Federal and State Governments on board

A spokesperson for the NSW Environment Protection Authority (EPA) said solar cells generally contain metals in small amounts.

Within a solar panel, these metals do not leach and as a result have not been found to present a risk to the environment.

“The use of solar panels to produce energy does not cause pollution; it is only when panels reach the end of their life that it becomes important to ensure sustainable reuse, recycling and safe disposal options.”

The role of the EPA is to identify and support circular economy opportunities, in particular the recycling of the materials to ensure they can be sustainably reused.

This includes providing grants to industry to progress technologies, as well as research opportunities to manage the waste stream.

“The EPA continues to work with industry to ensure that solar panels and the metals they contain are recovered and recycled. The NSW Government is supporting work with Federal and state governments to deliver a product stewardship scheme for solar panels.”

The NSW Government has also delivered the $10 million Circular Solar program to help facilitate a transition towards closed loop systems for solar cells and batteries, which includes construction of three solar panel and battery storage recycling facilities in NSW.