Despite years of fretting about Australia’s cyber security skills gap, the “miniscule” local industry is far too small to protect business and government targets, an expert has warned as a report finds the country “wholly dependent on skilled migrants” to plug that gap.

And even though the government talks about boosting the number of Australian tech workers to 1.2 million by 2030, the new report – which security firm StickmanCyber compiled based on an analysis of Australian census, ANZSCO and other labour force data from 1997 to 2024 – found that very few of these have specialised cyber security skills.

Industry body AustCyber recently counted 125,791 people employed in Australia’s cyber security workforce in 2022, but that includes a range of roles and just 51,309 of those are in ‘dedicated’ cyber security jobs.

Worse still, StickmanCyber’s analysis found just 11,387 Australians working in the specialised fields critical for businesses and executives who are increasingly obligated to maintain robust cyber risk management.

While pentesting is mandatory for compliance with PCI DSS standards that must be followed by any business handling credit card data, for example, there are just 200 penetration testers in Australia – along with 401 cyber governance risk and compliance (GRC) specialists, 641 cyber security architects, 1,561 cyber security engineers and 2,405 cyber security analysts.

By comparison, Australia has 43,940 developer programmers, 54,296 software engineers and 52,307 ICT project managers – confirming that while Australia has many people to implement technology solutions, the number of people capable of properly securing them is insufficient.

Security roles are also heavily concentrated in capital cities – with the report noting that there are “almost no rural cyber security professionals, despite it being an ideal industry for remote working” – and remain heavily skewed towards men, with women comprising just 16 per cent of cyber roles overall and just 5 per cent of specialised cyber roles.

Not a one size fits all proposition

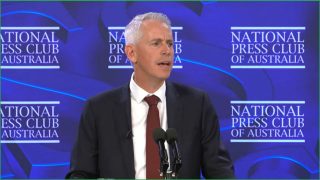

The figures highlight inconvenient truths about a cyber industry that, StickmanCyber CEO Ajay Unni said, “is woefully short of what’s needed to combat modern cyber security threats [and] incredibly low when you consider what an exciting and dynamic industry this is.”

Chronic nationwide shortages of all cyber security specialties – which have perpetuated Australia’s 30,000 strong cyber security skills gap – have been targeted with engagement efforts and programs to retrain workers from other industries.

Yet oft-cited numbers ignore the fact that highly specialised cyber security roles aren’t interchangeable, and take time to develop – and their absence, Unni said, has left Australia with a domestic cyber security industry that is “not fit for purpose”.

Unni – who trained as a programmer in India 30 years ago long before migrating to Australia and ultimately founding his own security consultancy – has seen many candidates who responded to the industry’s clarion call, and promise of strong salaries, but fail to demonstrate the necessary blend of technical and transformation skills.

“The technical aspect is quite easy,” he said, “but cyber is a transformatory program of work. It’s people, systems, processes – and year after year, organisations have failed to understand this.”

A lack of consistent professionalism hasn’t helped, either: “You can’t just rock up and say ‘I’m a doctor’ or ‘I’m a lawyer’,” he explained, “but cyber security is a non-regulated industry: anyone can do some courses online and say ‘I’m a cyber professional now’ – but it’s very obvious when there’s a lack of skill.”

“You can’t pretend that you have skills in this market.”

Just 3 per cent of all Australian ICT professionals actually have advanced cyber security skills, the analysis found – meaning that Australia has just one highly-skilled cyber security professional for every 240 businesses.

As a rule of thumb, Unni said, for every 100 people working in a company it supports, StickmanCyber needs 1.5 “cyber resources [of] all different skill sets” – meaning that securing Australia’s working population of 14.4 million would require a cyber workforce of 216,000 people.

That’s nearly 20 times the size of Australia’s “miniscule” cyber workforce, with the report noting that worker counts “are naturally even lower for the most specialised positions.”

“There is only one penetration tester for every 13,000 Australian businesses, yet pen testing is one of the most effective ways of finding weaknesses and hardening defences.”

Migrants are the key – but do they fit the lock?

Even as Australian universities and training institutions push to bring more people into the industry, businesses have increasingly turned to overseas workers for the skills they require – with 51 per cent of cyber security professionals born outside of Australia, and India by far the largest single source.

That, Unni said, means local industry “has become wholly dependent on skilled migrants to plug its technical skills gaps” – a reality that the government is slowly addressing by considering adding cyber roles to the Skills Priority List, and weighing changes to migration policy.

Australia has been here before, Unni said, recalling the sustained demand for developers that saw businesses snapping up anybody they could find – and quality and security often suffering.

Back then “there was this flood of education institutions that created a significant uplift in the workforce,” Unni explained, “but some were not that great quality, and some were extremely great quality – and we’re going to face the same problem with cyber.”

In cyber as in software development, he continued, “you can’t not have quality [when] you’re putting organisations and people’s lives at risk.”