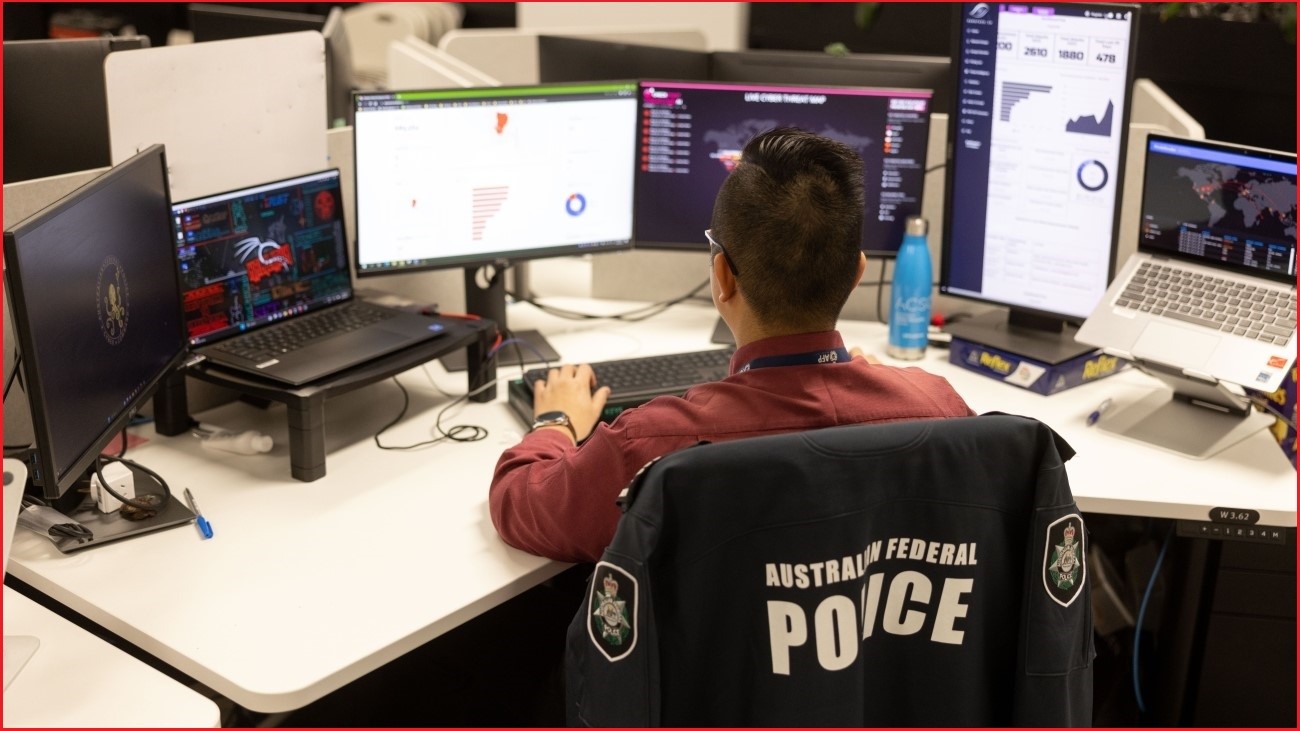

Cascading data breaches and murky cyber mechanisms have prompted Parliament to seek expert recommendations regarding the role of Australian law enforcement in responding to cyber crime.

Senators forming the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Law Enforcement (the Committee) are footing an inquiry into the capability of law enforcement to respond to cyber crime, drawing some 38 submissions from industry experts on topics from law enforcement and police upskilling to ransom payments and youth intervention.

While a long-lasting incline of scams and breaches in Australia has prompted government to reevaluate its cyber strategy, bulk up breach penalties, review the Privacy Act, and amend critical infrastructure laws, Helen Polley, Tasmanian Labor senator and Chair to the Committee, told Information Age cyber crime remains a “serious issue” which demands an “immediate response from government”.

“On average, one cyber crime is reported every 6 minutes, with ransomware alone causing up to $3 billion in damages to the Australian economy every year,” said Polley.

“In order for governments globally to tackle cyber crime, government must work with the community and industry to confront this global fight.”

Tackling ransom payments

During a 23 May public hearing, Reece Corbett-Wilkins, partner at global law firm Clyde & Co, called for clarification of existing laws around ransom payments.

Corbett-Wilkins advocated for decriminalisation of ransom payments, suggesting some circumstances – such as when a critical infrastructure operator is attacked and needs to restore its services – warrant a payout.

“These decisions are always made through gritted teeth, and it is one of the most unenviable positions to be in as a board director,” Corbett-Wilkins told the Committee.

Corbett-Wilkins described the stifling effect a ransom ban or punitive action could have on post-incident information exchanges with law enforcement, stating “organisations are deterred from sharing that information because of the risk of prosecution”.

“Decriminalisation of ransom payments will encourage information sharing with law enforcement from victims of ransomware attacks and those that pay. Controversial, I know,” Corbett-Wilkins told Information Age.

“[This] will result in more disruption, takedowns, and hopefully arrests.”

Reece Corbett-Wilkins of law frim Clyde & Co has called for clarification of laws around ransom payments. Photo: Supplied

Failing decriminalisation, Corbett-Wilkins called for law enforcement to make it “abundantly clear on the public record” that victims will not face prosecution for making a ransom payment, while fellow Clyde & Co partner Avryl Lattin pitched that government could provide safe harbour to companies who cooperate with law enforcement prior to making a ransomware payment and demonstrate having performed due diligence to avoid paying a sanctioned person.

Clyde & Co – which advises companies on incident response and deals with 100 to 150 ransomware incidents per year – has already observed a significant downturn in organisations paying ransoms, from 89 per cent in 2019 to approximately 30 per cent of Australian organisations now.

Early intervention for youth hackers

Debi Ashenden, cyber security professor and director at University of New South Wales (UNSW) Institute for Cyber Security, spoke to concerns of tech-savvy youth being drawn to cyber crime at an early age.

“A lot of under-16-year-olds get into cyber crime quite early – largely through cheating at online gaming, which is not illegal,” said Ashenden.

“They inadvertently, in a lot of instances, slip into cyber crime because they want to find out how to do more online.”

Ashenden suggested a range of law enforcement intervention options to the Committee, from making their presence known in criminal forums, utilising ad-words to warn youth when they conduct criminal searches, and having police carrying out cease-and-desist visits to the homes of at-risk youth.

Ashenden further raised the notion of upskilling the police by collaborating with external specialists – such as psychologists – so they can adequately perform intervention work and behaviour-change programs themselves.

“It's not about always relying on external people,” said Ashenden.

“It's also about finding ways to upskill the police in some of these areas, and it can be done.”

The professor noted such intervention work could help convert cyber criminals to cyber professionals – maintaining their interest in the field while ultimately helping to close Australia’s cyber security skills gap.

When asked about UNSW’s submissions, Polley told Information Age she encourages “all young people who are passionate about information technology and cyber security to consider a job within our security agencies and police force”.

Make crime reporting matter

A consistent issue raised throughout the hearing was the handling of cyber crime reports, which Ken Gamble, co-founder of cyber crime investigation unit IFW Global, said often “don’t make it to the right place”.

“It doesn't matter how much they've lost, whether it's $10 million or $100 million… it doesn't get investigated,” Gamble told the Committee.

Gamble noted while outfits such as Australia’s Joint Policing Cybercrime Coordination Centre have the mandate to look at cyber crime cases, the number of reports is simply overwhelming.

Gamble recommended a triaging approach for the “hundreds, if not thousands, of complaints” which arrive through the Australian Signals Directorate’s cyber.gov.au, suggesting many are from victims of the same overseas criminal syndicates and need to be assessed by similarity.

“There's no ability to identify the characteristics of that complaint as being identical to the next one and the next one,” said Gamble.

“They're being treated as individual complaints, and that's the biggest gap in the system.

“There's only really a handful of major syndicates that have been targeting Australia for the past decade.”

Gamble further suggested domestic authorities should investigate and prosecute cyber criminals outside of domestic borders – drawing reference to successful international initiatives out of the US and Germany – before further pointing out a lapse in state and territory police collaboration.

“We know that the New South Wales police and the Victorian police are not aware of some of the cases that the South Australian police and the Western Australian police are investigating,” said Gamble.

“There's no central ability to link these cases together.”

A government response is due within three months after the Committee tables its report on the inquiry, though there is currently no due date for said report.

The Committee is in the process of finding dates for additional hearings.