An Australian scientist and a group of international quantum researchers have been awarded Nobel Prizes for their work at the cutting edge of chemistry and physics, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences announced on Wednesday.

Richard Robson, an English-born professor who has worked at the University of Melbourne since 1966, will share the $1.77 million (11 million Swedish kronor) Nobel Prize in chemistry with fellow scientists Susumu Kitagawa and Omar Yaghi.

The trio were recognised for the development of a molecular architecture known as metal-organic frameworks, which link metal ions with organic carbon-based molecules while leaving gaps large enough for gases and chemicals to flow through, or to be captured.

The technology “may contribute to solving some of humankind’s greatest challenges”, the Nobel Prize organisation said, “with applications that include separating PFAS from water, breaking down traces of pharmaceuticals in the environment, capturing carbon dioxide or harvesting water from desert air”.

Heiner Linke, chair of the Nobel committee for chemistry, said, “Metal–organic frameworks have enormous potential, bringing previously unforeseen opportunities for custom-made materials with new functions."

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and Opposition Leader Sussan Ley publicly congratulated Robson at the beginning of Question Time in Parliament House on Thursday afternoon.

"It's an achievement for Professor Robson, but also a huge achievement for Australian science, for the Australian Research Council which has backed in this research over decades, and for Australia's research sector more broadly," Albanese said.

'Some people thought … it was a whole load of rubbish’

Development of metal-organic frameworks kicked off in the 1980s with Robson’s work combining copper ions with an organic molecule, which “bonded to form a well-ordered, spacious crystal”, the Nobel Prize organisation said.

Robson, who is 88 years old, said he first had the idea in 1974, but did not take it seriously until more than a decade later.

“Some people thought at the time — that’s in the middle 80s — it was a whole load of rubbish,” he told the organisation in a phone interview.

“Anyhow, it didn’t turn out that way.”

University of Melbourne vice-chancellor Professor Emma Johnston congratulated Robson and praised his "blue-sky research".

“Australia needs to recognise that this long-term fundamental research is what allows us to then translate that research into products, like the ability to store and transfer hydrogen safely," she said.

“As long as we continue searching for solutions for the world’s greatest challenges, fundamental research is essential."

Robson's work was built upon by his Nobel Prize co-winners Kitagawa and Yaghi, whose “revolutionary discoveries” made metal-organic frameworks more stable and modifiable, the Nobel Prize organisation said.

Robson is the first Australian Nobel laureate since astrophysicist Brian P Schmidt won a Nobel Prize in 2011 for helping discover the accelerating expansion of the universe.

Physicists opened doors for ‘next generation of quantum tech’

Two physicists who have recently helped Google maintain its position as a leader in quantum technologies were also awarded Nobel Prizes, alongside a colleague from the United Kingdom.

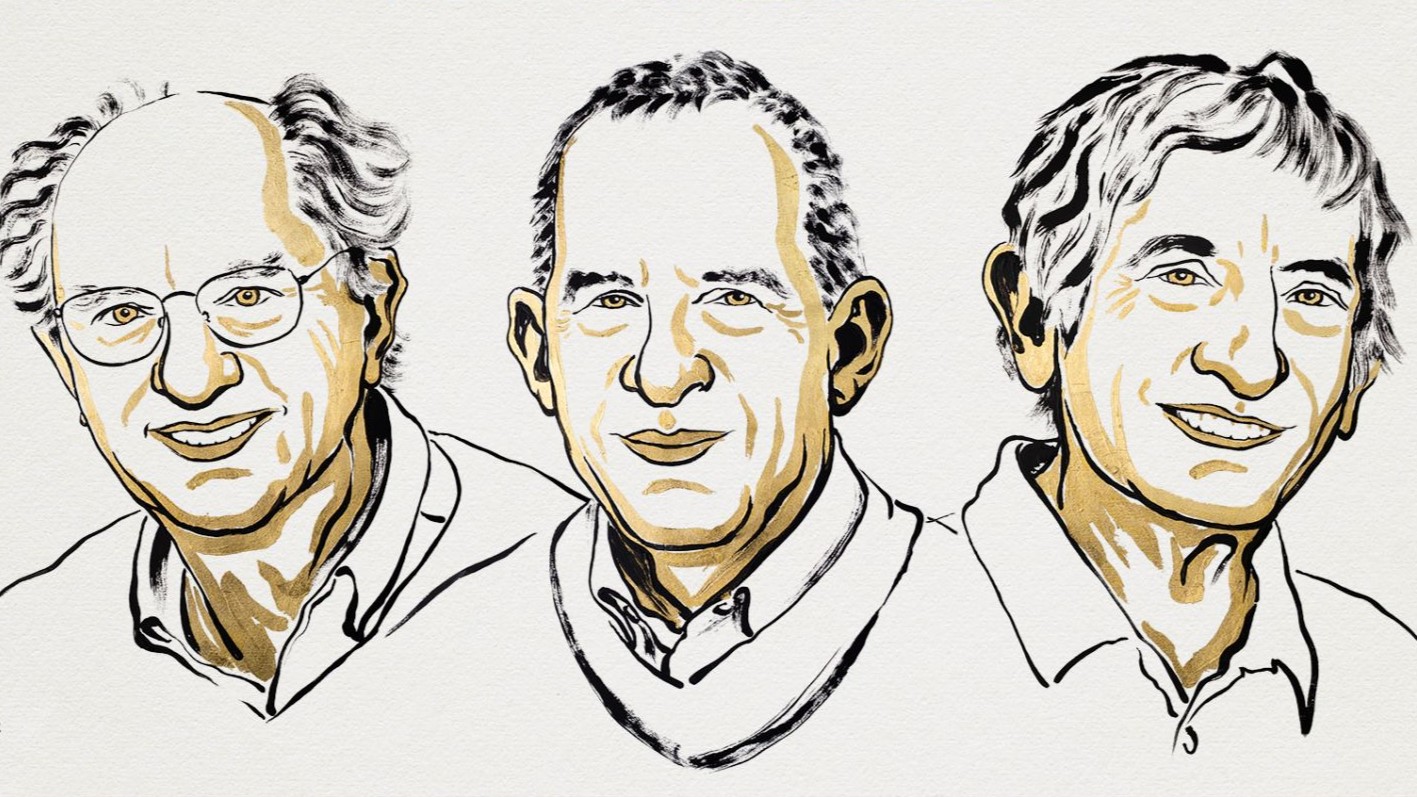

Google’s chief scientist of quantum hardware, Michel Devoret, and former Google employee John Martinis shared the Nobel Prize in physics with their fellow University of California researcher John Clarke.

The trio were recognised for experiments they carried out in the 1980s which proved the strange quantum mechanical phenomena seen in atoms and subatomic particles could be shown and controlled at a larger scale in an electrical circuit on a chip.

Their work “has provided opportunities for developing the next generation of quantum technology, including quantum cryptography, quantum computers, and quantum sensors”, the Nobel Prize organisation said.

Clarke told the organisation he was "stunned" by the award, and praised Devoret and Martinis as "brilliant people".

"I remember that we got invited to various conferences to give talks on this work, so it was clear to us that people appreciated what we had done," he said.

"I think the sort of ongoing significance for the following 40 years — I think we didn't have the remotest idea that would happen."

[L-R] John Clarke, Michel Devoret, and John Martinis share the 2025 Nobel Prize in physics. Image: Niklas Elmehed / Nobel Prize

[L-R] John Clarke, Michel Devoret, and John Martinis share the 2025 Nobel Prize in physics. Image: Niklas Elmehed / Nobel Prize

Marcus Doherty, the chief scientific officer at Australian quantum technology firm Quantum Brilliance, said it was “fantastic news to see Clarke, Devoret, and Martinis recognised”.

“Their work provided the foundation for and stimulated the development of a wide range of superconducting quantum technologies, which in many ways have built the momentum behind the second quantum revolution,” he said.

The push to build quantum computers which are more powerful than classical ones has seen the likes of Google, Microsoft, and IBM invest billions of dollars into research in the field.

Australian scientists have already contributed major developments in quantum chips at both Google and Microsoft, while American firm PsiQuantum is attempting to build the world’s first utility-scale quantum computer in Brisbane.

Last year's Nobel Prize for physics was shared between pioneering artificial intelligence experts Geoffrey Hinton and John Hopfield.