Peter Casper’s mobile phone is running hot.

It's only 10am and the Brisbane IT consultant has already received dozens of text messages about everything from unpaid bills to deliveries, bank deposits, removalist bookings, and two-factor authentication codes — but none of them are meant for him.

Peter is receiving hundreds of other people’s text messages each and every day.

On this particular Monday, the first one hits his iPhone at 12:48am, and the last at 11:59pm.

By the time the clock hits midnight, Peter's tally for the day stands at 431 new messages.

“You get used to it,” the 69-year-old tells Information Age.

A key reason why Peter gets so many messages is the makeup of his mobile number, which he says has belonged to him since it was first issued in the late 1980s.

The number, which Peter says he does not want to change, is a very simple and straightforward one.

An initially unforeseen result of the number’s simplicity is that an increasing number of people have provided it to businesses and organisations when they did not want to share their own, over the last three-and-a-half decades.

“My number is frequently inserted as a dummy number by people who don't know it's illegal to do,” Peter says.

“I get all sorts of weird and interesting things: deliveries that have been missed, even taxis and Ubers that are waiting for them, so I do get a lot of odd ones.

"I get messages about their missed Virgin flights, their changed Qantas flights.

“I do have a bit of fun with it though — someone tried to make a reservation at a cafe, so I've just cancelled it for them.”

While Peter only received a low number of unwanted messages back in the 1980s and 1990s, he says things “started picking up” at the turn of the century and have gotten significantly worse in the past 12 months.

Being an IT professional, he tracks most of the messages he receives in detailed spreadsheets.

But things can still get a little overwhelming, and Peter needs to automatically delete older messages from his phone because it receives so many.

“It started to make my phone lag,” he says.

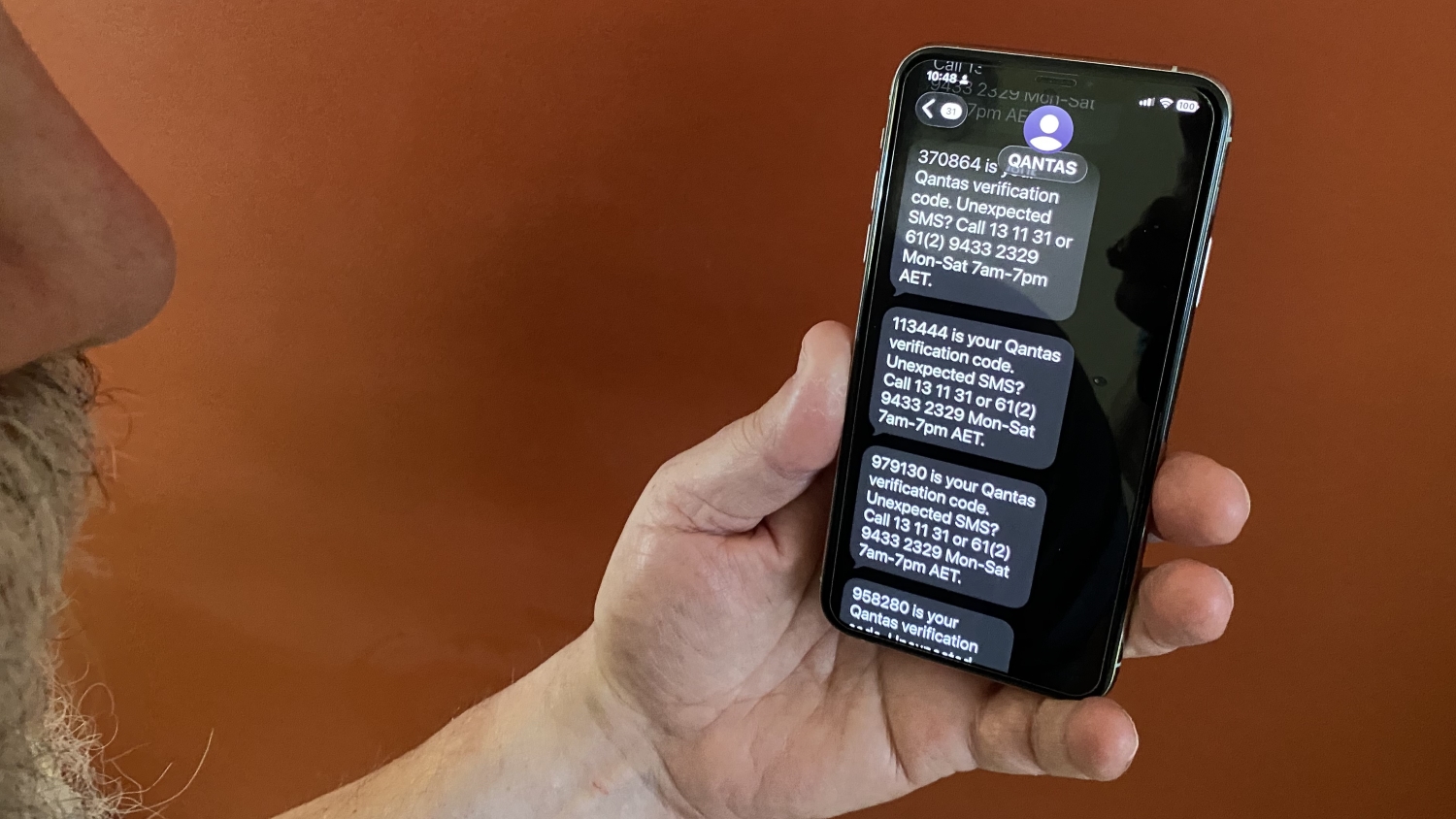

10,000 SMS in a month: Peter’s Qantas account nightmare

The worst offender for allowing SMS spam is Qantas, says Peter, who claims he sometimes receives more than 300 messages from the company each day.

Most of the messages are six-digit verification codes, which are typically sent out when someone is trying to log in to a Qantas Frequent Flyer account.

“Qantas … is just out of control — that’s now over 10,000 for the month,” Peter says.

“Maybe I’m getting 80 to 100 a day from other people, but nothing like the 300-plus I’m getting from Qantas.”

Information Age has seen an email in which a representative from the Qantas Frequent Flyer Service Centre referred to Peter by the wrong surname — instead calling him “Mr Moon”.

Peter believes this was the result of other people using his number in the Qantas Frequent Flyer system.

After being contacted by Information Age, Qantas identified that while Peter’s number was indeed being used by some of its other customers, the airline's IT team had also used the number in a large portion of test accounts without realising it belonged to someone — and an existing Qantas Frequent Flyer at that.

Qantas declined to comment for this story.

Peter Casper says Qantas has been the worst offender when it comes to unwanted text messages. Image: Peter Casper / Supplied

Peter says he suspected his number may have inadvertently been used for testing by Qantas, and he was receiving “a little bit less” correspondence from the firm after it had been pushed to investigate the issue.

“They really need to lock down these other flyers misusing numbers,” he says.

“It’s not just my number that gets misused, it’s other numbers as well, I’m pretty confident.

“… There is a bit of a problem with Qantas not testing the quality of its data properly, or enforcing that.”

As a Qantas Frequent Flyer, Peter’s personal information was compromised when the company suffered a significant data breach back in June.

While he says he has not noticed an uptick in text messages from Qantas since the breach, Peter worries about the security of the airline’s website, which still uses a four-digit login PIN instead of a password, along with a user's membership number and last name.

“I think they should get rid of the four-digit PIN and put in a proper password, but I think they should also limit their two-factor authentication or verification attempts,” Peter says.

“If they make putting mobile numbers into bookings optional, then people won’t be forced to put in dummy numbers when they don’t have a mobile, or when they don’t want to use a mobile.”

Qantas identified Peter's number was being used by other customers, and for testing by IT, after being contacted by Information Age. Image: Shutterstock

Regulator says 'unsolicited messages can be distressing’

Companies just “don’t listen” when Peter accuses them of breaching Australia's Spam Act by sending him messages meant for other people, and for allowing his number to be reused so many times, he says.

“ANZ bank just ignore all of my requests to stop spamming me, so their behaviour is a bit irregular.

“And BP are using me for testing, so I’m getting five messages from them every day – which is a bit annoying.”

Peter quickly rattles off the legislation, having clearly reviewed it and committed it to memory.

“Just putting in a random number, rather than putting in your real number, is a breach of the Spam Act of 2003, section 16, subsections six to eight,” he argues.

“But most people don’t know that.”

The Spam Act is overseen by the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA), which told Information Age it "understands that receiving unsolicited messages can be distressing and disruptive”.

While ACMA says the Spam Act “does not directly cover a circumstance where an incorrect number is given by a consumer”, the regulator says there are still some “general obligations” which apply to message senders.

“They must have consent to send such messages, and the messages must clearly identify the sender, provide a way to contact them, and provide a way to unsubscribe from further messages,” ACMA says.

“In such a case, where the person who has given consent appears to have provided an incorrect number for which they are not the account holder, the business is likely to be unaware they are sending messages to the wrong person.

“… ACMA notes that businesses may have obligations under ‘Australian Privacy Principle 10’ that set out that an entity must take reasonable steps to ensure the personal information it collects is accurate, up to date and complete."

A breach of an Australian Privacy Principle is an “interference with the privacy of an individual” and can lead to regulatory action and penalties, according to the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC).

Peter says he needs to automatically delete older text messages to prevent his phone from lagging. Image: Shutterstock

Why Peter doesn’t want to change his number

Peter says he is “fairly well known” by his telecommunications provider, Telstra, which he says has been “very helpful” — including understanding why he wants to keep his long-held but somewhat problematic mobile number.

He says he does not want to change his digits because he’s had the number for decades and primarily uses it for businesses purposes.

That’s despite his family members also sometimes receiving messages meant for someone else, as they have very similar phone numbers to Peter's.

“It’s just built up slowly, so they’re used to it,” he says.

“My wife gets two or three a week, which she just ignores.”

Peter says his son, who is also in the IT industry, is expected to one day inherit his troublesome phone number.

As a father, he says he would appreciate it if people stopped putting his number on their accounts before that handover occurs.

“That would be nice,” he says.