Dame Stephanie “Steve” Shirley, one of the UK’s most visionary technology pioneers, philanthropists, and advocates for women in the workforce, passed away on 9 August after a short illness.

She was 91.

Born in 1933 in Germany, ‘Vera Stephanie Buchthal’ as she was known then, arrived in Britain at the age of five via the Kindertransport, escaping the horrors of the Holocaust.

Separated from her parents, she was one of nearly 10,000 Jewish children saved from Nazi-occupied Europe and was fostered by parents in the UK.

“I decided to make mine a life worth saving,” she would later say.

Although she was able to later reunite with her birth parents, she sadly revealed she “never bonded with them again”.

The revolution begins

In 1962, frustrated by the limitations placed on women in the workplace, Shirley founded Freelance Programmers, a revolutionary software company – and a radical concept for its time.

Not only was Freelance Programmers one of the first software startups in the UK, but it was also staffed almost entirely by women, including transgender and gay women.

Many of these women had left the workforce due to marriage or motherhood.

“And people laughed at the very idea,” she said, “because software, at the time, was given away free with hardware.

“Nobody would buy software, certainly not from a woman.”

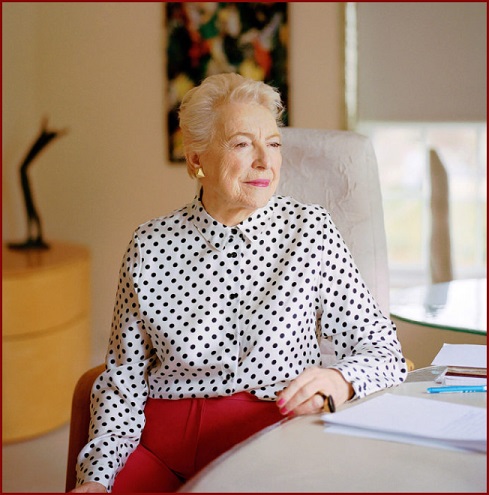

Dame Stephanie Shirley pioneered work for women. Photo: Supplied

At a time when women needed their husband’s permission to open a bank account, Shirley gave them careers, flexibility, and independence.

She pioneered remote working decades before it became mainstream, asking only one essential question in early job interviews: “Do you have access to a telephone?”

“We pioneered the concept of women going back into the workforce after a career break,” Shirley said.

“We pioneered all sorts of new, flexible work methods: job shares, profit-sharing, and eventually, co-ownership when I took a quarter of the company into the hands of the staff at no cost to anyone but me.”

Shirley’s company thrived by doing challenging work; scheduling freight trains; building control systems; even programming the black box flight recorder for Concorde.

Despite starting on her dining room table with what she described as the equivalent of “£100 and a borrowed house,” the company grew to employ over 8,500 staff and was eventually valued at more than $3 billion.

Her leadership turned 70 of her employees into millionaires when she shared equity in the business.

To counter workplace sexism, she began using the name “Steve” on business correspondence – a moniker that would stick for life – because letters she sent as “Stephanie” would go ignored.

She once joked in a TED talk, “You can always tell ambitious women by the shape of our heads – flat from being patted patronisingly.”

In 1975, ironically, the very success of her pro-women policies ran afoul of new equal opportunity legislation, forcing her to begin hiring men.

But by then, Freelance Programmers (which later became Xansa) had already proven that flexible, women-led, remote-first companies could succeed on the global stage.

Shirley was the first female President of the British Computer Society (1989–90), and was awarded a Distinguished Fellowship in 2021.

Dame Stephanie Shirley's book, Let it Go. Photo: Supplied

Philanthropy in all its forms

Shirley’s professional triumphs were matched by personal trials. Her only child, Giles, was profoundly autistic and never spoke.

That experience led her to become a passionate advocate for autism services.

She founded multiple charities, including the ground-breaking Prior’s Court School, and invested millions into autism research and care.

“Whenever I found a gap in services, I tried to help,” she said simply.

Her philanthropic efforts extended well beyond autism.

She established the Oxford Internet Institute to study the societal impacts of technology and gave away the majority of her wealth — describing philanthropy as her life’s second act.

“Philanthropy is all that I do now,” she once remarked. “I need never worry about getting lost because several charities would quickly come and find me.”

In her lifetime, Shirley wrote three books: an autobiography Let it Go in 2012, My Family in Exile in 2015, and a collection of her speeches over the years, So To Speak in 2020.

Recognition at the highest level

Among countless honours, Shirley was appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire in 1980, Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 2000 for services to information technology, named Member of the Order of the Companion of Honour in 2017 for services to the IT industry and philanthropy, and became a Fellow of the Royal Academy of Engineering in 2001.

Shirley leaves behind a world more open to women in leadership, working from home, neurodiversity, and building wealth for purpose rather than power.