There is a dire shortage of talent in the information security industry.

Today, industry roles command big salaries, but also bigger workloads.

When you read articles about ‘the best jobs’ or ‘highest paying jobs’ to consider, information security is always in the top 10 of the list.

How does this industry sustain current security professionals and prepare the next generation?

Here, I look at what current professionals can do, and offer sound advice for preparing the next generation of security pros.

Malicious cyber activities are becoming very common.

Some have gone so far as to say that this form of crime knows no bounds.

It is global and unlimited, like the internet itself.

The deficit of a well-developed, skilled workforce makes government and businesses’ recruitment efforts very difficult.

Developing sophisticated technical capacities has become a priority for US and global industries and governments.

The role of educators

No-one plays a more important role in preparing the next generation security professionals than educators and trainers.

We need to make sure existing education gives students a holistic view of cyber security with focus on relevance and proficiency.

The complicated state of cyber threats requires a learning methodology engendering critical thinking and deeper understanding to defend against increasingly complex cyberattacks.

A number of shortcomings exist in the conventional classroom training model in creating efficient and reliable cyber security professionals, according to the Software Engineering Institute.

Going forward, we will be facing increasingly interdisciplinary and multi-faceted challenges.

These will necessitate knowledge in different fields and areas, including law and law enforcement, criminology, engineering, computer science, to name a few.

This is hardly a surprise, as the main elements of cyber security – technical perfection, process, and people – must be supplemented by the capability to manage shortcomings.

Deterrence Doctrine and SPC (Situational Crime Prevention) theories

Information system researchers analysing security compliance and behaviour use the deterrence doctrine, according to which the likelihood of violations is inversely proportional to the perceived risk and punishment.

A review found that this theory has been the most-cited one in Centre for Internet Security (CIS) security literature over the past three decades.

According to this literature, one must increase awareness of an organisation’s efforts to limit ICT abuse and of the likelihood and/or extent of sanctions in order to reduce ICT violations.

The Situational Crime Prevention (SCP) Theory is widely used to study cybercrime and reduce criminal activities perpetrated or otherwise related to employees.

Most crimes are opportunistic and occur when a motivated offender detects a suitable and unguarded (or incapably guarded) target.

Proponents of the SCP theory find violators to be rational decisionmakers who carry out an analysis of costs and benefits before committing a crime.

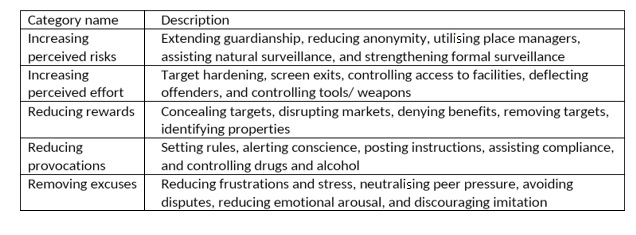

Accordingly, the SCP theory outlines five broad categories of efforts to counteract cybercrime that security professionals should make. They are presented in the table below:

Table 1. Categories of efforts to counteract cybercrime, according to SCP

The US government established a cyber skill task force to address the crisis in human capital in the field of cyber security, improve retention and recruitment of cyber security professionals, and identify the best ways to create and support a national cyber security workforce.

This initiative gave rise to the NICE Framework: a proposal to group, organise, and describe cyber security tasks.

The framework is comprised of seven categories covering 31 specialty areas, as well as details regarding work roles, skills, abilities, knowledge, and tasks.

It has become a good starting point for developing a central cyber security curriculum and a useful categorisation of topics and related skills.

Cyber security exercises

The NICE Framework and the Situational Crime Prevention Theory have been combined to design and deliver cutting-edge tools and strategies.

One notable example of how these are used is the Cyber Security Exercises (CSE), an offense/defense environment, in which students are grouped and get a virtual machine to host HTTP(S), FTP, SSH, and other services.

These services can then be accessed by other groups.

The CSE aim to reflect real-life environments for students to apply their skills.

The approach of CSE architecture has proved useful for translating theory into practice.

More specifically, CSE are elaborate learning experiences aimed at developing competence and expert knowledge through simulation.

They are associated with a number of pedagogical issues, including design of exercises and training outcomes and evaluation.

Training effectiveness can be improved based on analysis, observation, and integrating educational knowledge and focus at each stage of the life cycle of CSE, including planning, feedback, and implementation.

It’s necessary to measure change systematically in order to improve CSE, ranging from organisational change to changing customer experiences.

Scenarios to help prepare cyber security professionals

According to the Center for Internet Security, technical professionals, admins, and users share the responsibility for security.

The CIS has prepared a series of tabletop exercises to help cyber security professionals and teams secure their systems by means of tactical strategies.

These exercises are intended to assist organisations in comprehending various risk scenarios and preparing for potential cyberthreats.

The exercises I’m about to present do not take very long to complete.

They are a convenient tool to develop a cyber security mindset.

They consist of six scenarios which list relevant processes, threat actors, and impacted assets:

Scenario 1: Malware infection

While using the company’s digital camera for work, a staff member takes a picture that he then moves to his personal computer.

He does so by inserting the SD card, which while connected to his PC becomes infected with malware.

Unsuspecting of this fact, he re-inserts the card into his work computer and the malware spreads throughout the organisation’s system.

The question is how the company will now deal with this issue.

To answer this question, one needs to consider a few additional ones.

The first of these is who you’d need to notify within the company’s structure.

It’s important to identify the vector of the infection and to establish a process for doing so.

In addition, what should management’s reaction be?

Are there any other devices that could present a similar risk?

Does the company have policies and training to prevent this and do these apply to all storage devices?

At the core of this scenario is user awareness and detection ability.

Scenario 2: Quick fix

Your underpaid and overworked network administrator is finally going on vacation.

Just as she’s packing the last item in her suitcase, her boss asks her to deploy a critical security patch.

She comes up with a quick fix so she can make her flight.

Soon after that, your service desk technician tells you people have been complaining that they can’t log in.

It appears the admin did not run any tests for the critical patch she installed.

Does the technician have the skills and knowledge to handle the issue?

If not, whom should it be escalated to?

Does the company have a formal policy to change control in place?

Is staff sufficiently trained to escalate such issues?

Does the company have any disciplinary measures to take if an employee doesn’t adhere to policies?

In the event of unexpected adverse impact, does the company have an option to rescind patches?

This is one of the threats that impact an organisation’s internal network.

Patch management is the process tested.

Scenario 3: An unexpected hacktivist threat

In the wake of an incident involving accusations of use of excessive force by authorities, a hacktivist threatens to attack your company.

You have no idea what kind of attack they are planning.

What measures can you take to best protect your organisation?

What is your reaction?

Again, you need to look at the potential threat vectors.

Perhaps certain vectors have been common in the last few weeks or months.

What methods can be used to prioritise threats?

You must alert your help desk as well as other departments within the organisation to the threat.

A bulletin board is a nifty solution.

You need to check your patch management status if you haven’t already, and augment IDS and IPS monitoring.

Think about getting outside help if you don’t have the resources to manage all this by yourself.

Ask yourself what companies or organisations can help you analyse any malware identified.

It’s evident that your response plan should account for such situations.

Your preparation is the process tested.

Your security professionals may be the first line of defense, but as you can see, they can’t be the only one.

Your whole organisation needs to be involved, active, adequate, and compliant when security is at stake.

Scenario 4: Financial break-in

Following a financial audit, it emerges that a few people who have never actually worked for the company are receiving paychecks.

You conduct a review, which shows someone added them to the payroll a few weeks earlier, simultaneously, using a computer in the finance department.

How do you react?

The strategy starts with investigating how these people were added to payroll.

Let’s say there was a break-in at the finance department prior to the addition.

A few computers were stolen.

However, there was no sensitive data on them, so the incident did not get serious attention.

Upon further and more in-depth review, it emerged that all of your employees were being charged a new “fee” of ten dollars and someone was siphoning this money to an offshore account.

Nobody noticed because it’s just ten dollars.

It’s important to outline possible actions to take after any break-in.

Decide who needs to be notified and whether you can assess the full extent of damage.

Can you audit your physical security system?

Can you see what information (credentials) was stored on the stolen computers?

How can you contain the damage and how is it best to notify staff of it?

Last but not least, is it possible to compensate one’s employees?

Here, response to incidents is the process tested.

More specifically, we’re dealing with an external threat affecting our financial information.

Scenario 5: Cloud compromise

One of the departments of the company often uses an external cloud to store huge volumes of data, some of which sensitive.

Recently, you found out this storage provider suffered a breach leading to exposure of large amounts of data.

It may be that all user data stored in this cloud has been compromised, including all user passwords.

Consider whether the company has existing polices taking third party cloud storage into account.

If so, is it right to hold the company accountable for the data breach?

What should your management’s reaction be?

If the breach occurred on your own LAN, would any of your procedures and actions be different?

When and how would you inform your users?

What do you tell them, if anything?

This scenario tests response to incidents and deals with an external threat just like the previous one.

The difference is that it affects the cloud, not financial information.

Scenario 6: Natural disaster and ransomware

Your company has been hit by some kind of disaster.

As you struggle to manage it, you suffer another blow: a ransomware attack that renders your computer systems inoperable.

What do you do?

Every organisation should have a disaster recovery plan and a plan to continue operations.

What’s more, your organisation should conduct an annual simulation to make sure these plans are adequate and run smoothly.

Your emergency response plan should detail the steps to take after a ransomware attack.

If backup isn’t an option, what steps will you take?

Does your ERP take both situation severity and the financial implications of a cyber security breach into account? It should.

A ransomware attacker (or any other type of cyber security attacker for that matter) will demand funds in cryptocurrency in the vast majority of cases.

It’s easy to see why – they are untraceable.

Ask yourself if your organisation will be able to acquire cryptos, how much you can get, and the extent, to which cryptos will be accessible.

You need to be able to route emergency processes or communications through a neighbouring entity.

Who must you notify and how will you do it?

There may be line congestion due to increased phone traffic.

This last scenario tests your emergency response to an external threat.

Tips to organise exercises

One single person must be tasked with facilitating the respective exercise.

Each scenario should be broken down into meaningful and digestible learning units.

To make sure the group understands the scenario, read it out loud and try to facilitate a discussion of the ways, in which the members of the group would handle it.

As you talk, focus on key learning points.

Not only security professionals, but also representatives of other relevant business units should take part.

Identify any gaps and follow up on them.

Set exercise goals

Start by identifying the goals and desired outcomes of each exercise.

It’s impossible to plan a meaningful initiative without clear goals.

Your goals will enable you to structure the scenarios clearly and see if your organisation has the capabilities required to defend itself against cyberthreats and operate within a hostile environment successfully.

It’s of paramount importance to establish a baseline for each scenario because guiding principles, procedures, tactics, and tools differ from organisation to organisation.

Make sure info networks and systems operate in support of the scenario in question.

This is the main purpose of conducting cyber security training that involves numerous entities.

Plan exercises properly

Once you’ve established your goals, you can proceed to look at what sort of exercise would match them.

A cyber exercise can transpire within a bigger exercise on a general operational network or as a stand-alone event on an isolated one.

The former requires additional coordination to make sure it supports the bigger goal through controlled impact to the comprehensive network.

In general, these are the most important objectives:

● Evaluate effectiveness of incident reporting and analyse guides to remedy deficits

● Before the exercise begins, determine the effectiveness of the cyber training provided to participants

● Evaluate the participants’ ability to detect and counteract hostile acts

● Establish a contingency plan to cope with full or partial IT systems loss

● Determine scenario planning and execution success

● Evaluate your organisation’s capability to recognise the full operational impact of cyberattacks and introduce the right recovery practices and procedures for the exercise

● Capture workaround for loss of trust in IT systems and understand its implications

● Reveal and remedy deficiencies in cyber operations policies and procedures

● Reveal and remedy cyber security system weaknesses

● Determine what capabilities or enhancements are required to protect an information system and establish support for operations in a hostile environment

● Enhance cyber coordination, readiness, and awareness

● Determine if your interventions will help attain training goals

How to evaluate training outcomes

The outcome to aim for is enhancing awareness of and evaluating responses to different cyber threats.

Outcomes should be connected to the main goals of the exercises.

The solutions to the common cyber security issues detailed above should be customised to meet desired outcomes.

For example, exercise planners must develop one or more scenarios that involve threats to IT assets if the exercise focuses on evaluating the ability to detect and react to hostile activity.

These scenarios should be designed to stimulate participants and elicit responses in line with the goals and desired outcomes of the exercise.

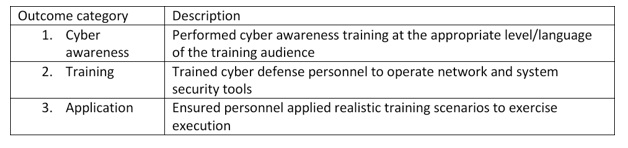

Table 2. Desirable Outcomes

In terms of the first outcome, network administrators, cyber security administrators, end users, and system administrators have to undergo cyber awareness training that includes response to incidents, cyber threats, and responsibilities.

Specialists must provide the right cyber tool training required by security professionals for the exercise.

This should include procedures (detection, log review, and incident response), security devices (antivirus, firewalls, IDS), and accreditation policies.

Finally, the stage of application involves use of unclassified techniques and tools that security professionals can share.

These can include fake websites, social engineering, spear phishing, internal network manipulation, and/or physical access attempts.

The purpose is to run the exercise in line with the scenario and its goal.

Formal education

In-house training isn’t always sufficient; formal education is often necessary.

For example, Fairfield University in Connecticut recently launched a Master of Science program in Cyber Security, which offers students practical experience using real-world apps.

The university’s cyber security lab helps enhance coursework complexity, motivating students to solve complicated problems and ultimately equipping them with the technological and critical thinking skills they need to mitigate, monitor, and prevent cyber security risks.

Being able to work under pressure is very important because security threats thrive off distraction and human error.

The right training and education will prepare the next generation of cyber security professionals by simulating real-world challenges realistically.

Nishant Srivastava, MACS CP, is an Australian cyber security expert currently based in New York City. He began his career in IT with the ACS scholarship program a decade ago. He is also a board member of the Information System Security Association (SSA) for the New Jersey chapter.