When social media powerhouse Facebook changed its name to Meta last October, CEO Mark Zuckerberg was trying to stay ahead of his company's biggest problems.

Facebook's userbase was in decline and Apple's privacy changes were putting negative pressure on its advertising revenue.

The re-brand was a way of moving the company away from Facebook – and all the connotations that name carries – and toward the ‘metaverse’, a term science fiction writer Noel Stephensen coined to describe a virtual reality (VR) world in the early 1990s.

At the core of this change is Reality Labs, Meta’s own research and development team that is working on tech to literally read minds in order to build out its augmented and virtual reality hardware.

Last week, a panel from Meta’s Reality Labs briefed media about how its teams were trying to solve the ‘visual Turing test’.

This is the phrase used internally as shorthand for photorealism because Meta’s stated goal is to display, fully immersive virtual environments that are indistinguishable from reality.

“Displays that match the full capacity of human vision are going to unlock some really important things,” Zuckerberg said.

“The first is realistic sense of presence – that's the feeling of being with someone or in some places as if you're physically there.”

Zuckerberg is pitching the next generation of video calls in which mixed or virtual reality devices let you feel like you’re in a room with another person, or at least with their “photorealistic avatar”.

In his ‘metaverse’ future, you and your family or colleagues will share the same virtual space while being geographically isolated.

Workplace technology company Cisco is trying to make the same vision a reality product with its Hologram video calls – a piece of tech that, in its attempts to make another person feel ‘closer’, currently makes them feel more isolated and ethereal than the video calls we’re used to making every day.

For Meta, the main problem with modern VR is its fidelity and is primarily a hardware problem.

“VR introduces a slew of new issues that simply don’t exist with 2D displays,” said chief scientist of Reality Labs, Michael Abrash.

“[Things like] vergence accomodation conflict, chromatic aberration, ocular parallax, pupil swim – and before we even get to those, there's the challenge that our displays have to fit into compact, lightweight headsets and run for long periods off batteries in those headsets.”

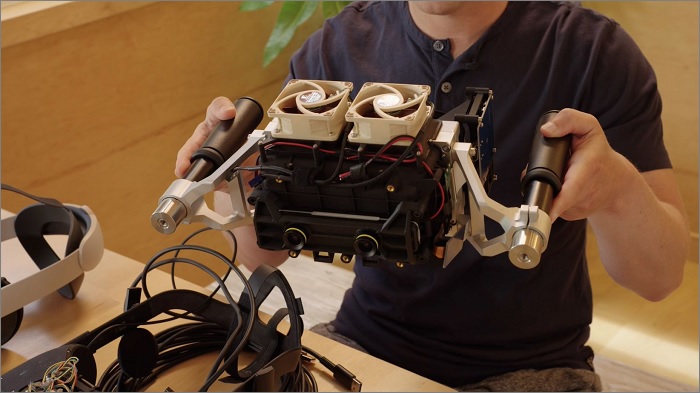

The Starburst prototype is an impractical proof-of-concept device. Image: supplied

As such, the development of photorealistic VR headsets isn’t just a matter of shrinking down existing displays to fit on a headset.

One interesting problem is focus.

Your eyes naturally focus differently on objects depending on how near or far they are.

This isn’t a problem for fixed distance 2D displays like on your phone or laptop monitor, but in VR it means a greater need to dynamically render all objects depending on where your eyes are looking.

Meta’s solution is to test using varifocal lenses that adjust automatically as you look around virtual worlds.

Similarly, modern VR headsets aren't particularly bright so Meta began looking at ways of going beyond LEDs and is trying to make small, cheap lasers that will significantly increase the brightness of headsets.

Meta has a long way to go before it can fit all of its photorealistic fixes – like lasers and varifocal lenses – onto one headset.

In fact, Meta is expected to delay its next-generation of headsets and glasses for at least another couple of years.