When you buy a product, you expect to be able to repair it.

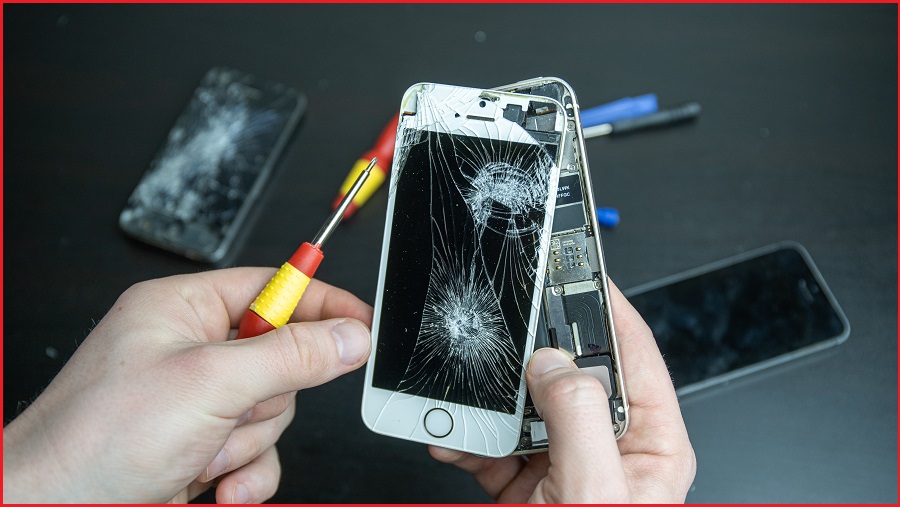

The problem is, many modern products are designed so that you can’t fix them. Vital parts are inaccessible.

Or you have to go through the manufacturer, which may well just give you a new one.

The end result: millions of expensive products, from cars to phones to appliances, end up in the rubbish tip.

At the most extreme, manufacturers actively prevent you from repairing their products at the local mechanics.

You can see why some manufacturers prefer the world to work like this.

If you can’t repair your washing machine, you have to buy a new one. But it’s a hidden cost to all of us – and a huge source of avoidable waste.

That’s why many countries and jurisdictions are introducing laws enshrining your right to repair products.

Last month, the EU passed a “right to repair” policy. In the United States, 26 states have proposed laws.

But Australia is dragging its heels.

Make, use, dispose, repeat - works for the electronics industry, but doesn’t work for the planet! So we went all in and designed smartphones to break this cycle. This World Consumer Rights Day we support the right to repair and we have the perfect 10's from iFixit to back it up! pic.twitter.com/JbogPh0gif

— Fairphone (@Fairphone) March 15, 2023

So what’s the hold-up?

In July 2021, Australia passed its first right to repair laws, a mandated data-sharing scheme to make it possible for independent mechanics to get access to diagnostic information.

This was a good start, but limited to one sector.

The Productivity Commission assessed the case for a broader right to repair almost two years ago and released its final report in late 2021.

Here, it pointed to the opportunity to give independent repairers:

"greater access to repair supplies, and increase competition for repair services, without compromising public safety or discouraging innovation."

In October last year, the new environment minister Tanya Plibersek and state environment ministers put out a joint commitment, calling for Australia to recognise the scale and urgency of environmental challenges and

"design out waste and pollution, keep materials in use and foster markets to achieve a circular economy by 2030."

A circular economy would mean effectively ending waste.

Instead, waste streams are turned back into useful products. Many other countries are working to cut waste to a minimum.

The design of products is also a vital way to reduce waste going to landfill or, worse, the oceans.

Redesigning products to make them repairable will prolong their useful life, value and functionality.

Labor has made positive sounds. But we are yet to see the promised action.

What are other countries doing?

Plenty.

America’s proposed right to repair laws vary by state in terms of what industries they cover. They range from the first ever right to repair agricultural equipment in Colorado through to all-encompassing consumer-focused laws.

Less than a month ago, the European Union passed a right to repair policy aimed at making it easier to access repairs for appliances and electrical goods. EU justice commissioner Didier Reynders estimated the laws would save consumers $288 (€176) billion over the next 15 years.

But consumer advocates say the laws don’t go far enough.

📢 The @EU_Commission finally launched its long-awaited #RighttoRepair proposal

— Right to Repair Europe (@R2REurope) March 23, 2023

➡️Despite some good steps, the proposal does not address affordability of #repair, anti-repair practices & is a missed opportunity to make the #RighttoRepair universal!

🔽Quick analysis in the🧵 pic.twitter.com/E1im85z6kq

Canada is looking to reform its copyright act to introduce a consumer right to repair electronics, home appliances and farming equipment.

India, too, is exploring right to repair laws.

Why have these laws taken so long?

The main reason? Is it just government inaction or opposition by industry?

There is a long and predictable list of opponents to right to repair laws.

By and large, opposition comes from the manufacturers who see these laws as a hit to their bottom line.

Companies often deny there are any obstacles to repairing their products. Or they cite concerns over intellectual property, safety, security or environmental grounds.

But underlying all these arguments is a simpler reason: companies would make less money if consumers repaired rather than bought a new product, and less money again if they lose their hold on who can repair specific products.

At present, companies win and consumers lose. When companies can direct you to only use an authorised repair outlet, there’s no risk of competition driving down the cost of repairs.

Manufacturers often respond with industry-led, voluntary initiatives such as the recent agreement between tractor giant John Deere and lobby group American Farm Bureau.

The problem is, voluntary agreements often don’t work and regulation is needed for the manufacturers to act upon their promises.

As Australia grapples with its thorny plastic waste crisis, it’s a timely reminder of the need to go faster.

Environment minister Tanya Plibersek used the collapse of the soft-plastics recycling Redcycle to call on industry to do more on recycling – or see new recycling regulations introduced.

What would right to repair laws mean for Australia?

If we gain the right to repair, we could:

- expect new products to be able to be repaired

- expect to be able to repair products anywhere – not just at manufacturer centres.

This would save us all money, and divert significant volumes of waste from landfill.

If we return to the old ways of repairing rather than throwing out products, we would also trigger a rebirth of repair-based businesses, employment growth and up-skilling.

But these benefits will only arrive if the government ensures any such laws are binding.

Leanne Wiseman is a Professor of Law at Griffith University.

John Gertsakis is an Adjunct Professor at the University of Technology Sydney.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article here.