Whether it’s Microsoft Copilot summarising an email from your doctor or Hinge offering AI “Convo Starters” to impress a date, there’s a good chance AI will be involved in your private communications in 2026.

There’s just one problem: did we actually consent to this?

Big Tech’s ambitions for AI are obvious. But Abhinav Dhall, associate professor in Monash University’s Department of Data Science and Artificial Intelligence, says many people are “not clearly aware” when AI systems are handling their data.

“AI may be analysing a conversation involving two users, even though only one of them has enabled or even noticed the feature,” said Dhall.

“As a result, one or both parties may not fully understand what consent has effectively been given, or how their communication is being used.”

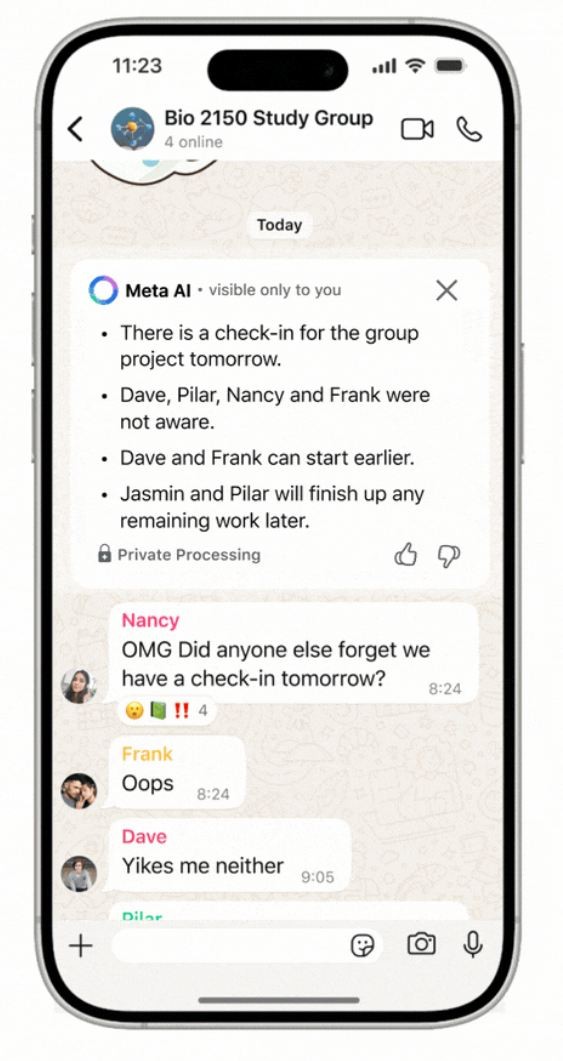

You may have noticed in recent months, for example, that tech giant Meta’s AI can summarise your chats on such apps as Instagram, Messenger and WhatsApp.

Your private messages, as summarised by Meta AI. Source: WhatApp

When using the feature on Messenger, Meta explains unread messages in a chat “will be shared with Meta AI to create a summary that will only be visible” to the requesting user.

And while a Meta spokesperson recently confirmed “private messages with friends and family” are not used to train the company’s AIs, messages which are willingly shared by “someone in the chat” are fair game.

Meta did not respond to Information Age when asked about its approach to consent.

I didn’t write that email for an AI

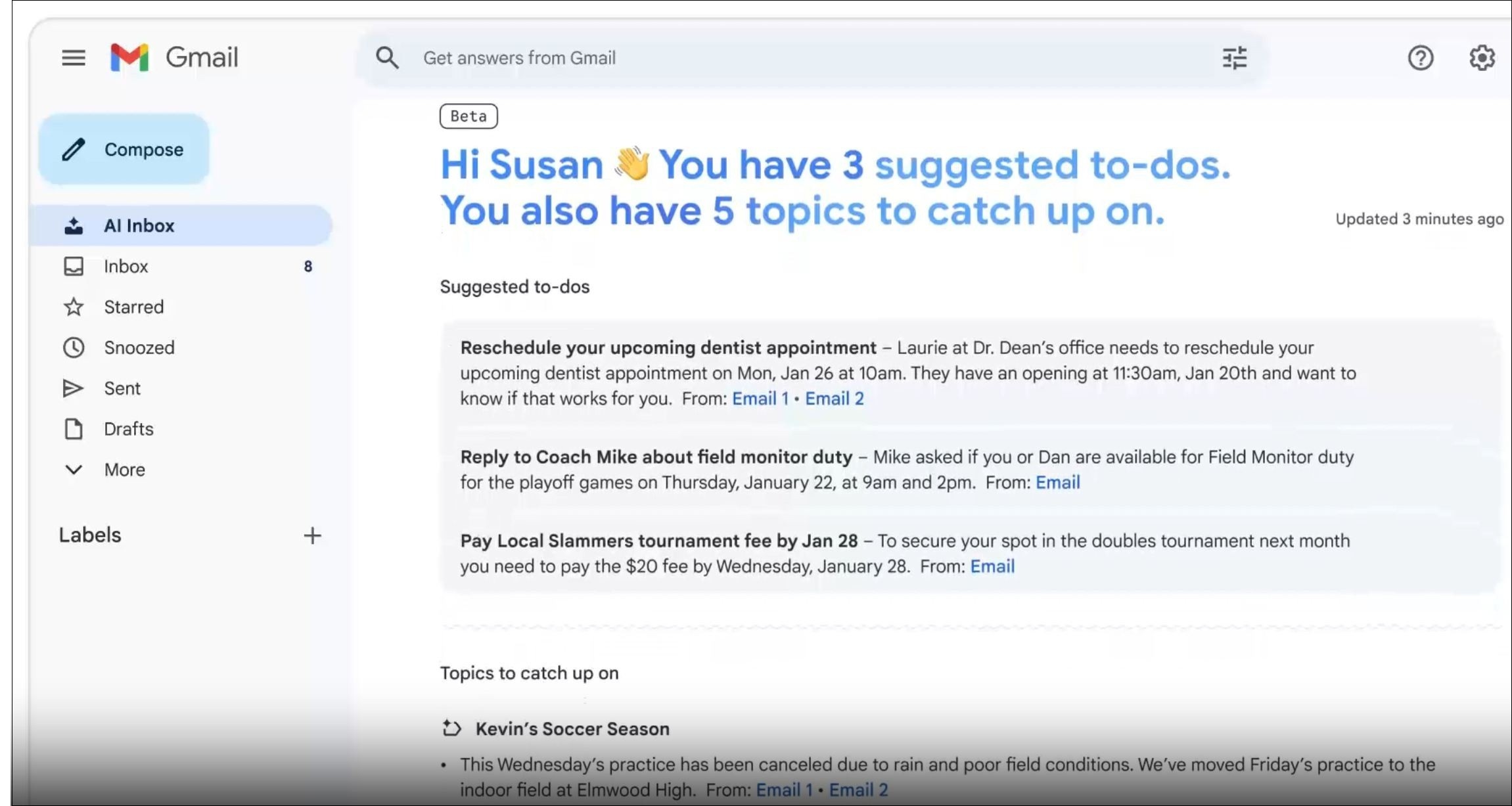

Recently, tech giant Google began its rollout of ‘AI Inbox’, a new feature which reimagines the traditional email inbox as a series of to-do items and AI-generated summaries based on your highest priority emails.

The tool is one of many AI features Google is using to push Gmail into the ‘Gemini era’, where the company’s flagship large language model (LLM) will serve as a “personal, proactive inbox assistant” that helps draft, summarise and triage your emails.

For senders, this means private emails written to users of Gemini in Gmail may be processed, at some level, by Google’s AI.

Gemini picks out important emails and reads them on your behalf. Source: Google

Though users generally don’t need to disclose when they engage such tools, Dana McKay, associate dean of Interaction, Technology and Information at RMIT's School of Computing Technologies, believes senders “should have to consent” before their private emails can be read by a recipient’s AI.

“Some emails contain confidential information, such as medical or commercially sensitive information, that they want to keep private,” said McKay.

“Sometimes, we just want our communications to be person to person.”

Though a Google spokesperson assured Information Age “when you use Workspace Gemini features, including those in Gmail, we do not use your personal content to train our foundational models”, Dhall suggests there are still privacy implications to consider.

“The sender’s words are being processed,” Dhall said.

“AI systems can do more than a human reader – they can summarise, extract details, and in some cases store patterns.

“[This] changes privacy expectations.”

When asked how Google approaches consent, a spokesperson pointed Information Age back to an existing “Gemini era” blog post.

Clickwrapping consent

Notably, McKay said she did not think people broadly “understand enough about AI to give meaningful consent”.

“I also think we face problems of click-wrapped consent, as we do with many tech services,” she said.

“People can't choose what to consent to, and terms and conditions are long and arduous.”

Dhall added that as AI features are increasingly being “embedded” into popular platforms, users may find themselves ‘agreeing’ by default, often “without a clear moment of informed choice”.

“This creates a critical need to redefine how consent is obtained, such that it is more inclusive and understandable, rather than buried in long documents, broad terms of service or enabled by default,” said Dhall.

Is it legal?

James Patto, founder of Melbourne-based law firm Scildan Legal, said although the legality of AI tools can look murky at first, Australia’s existing legal frameworks are more concerned with how personal information is being used.

“Australia doesn’t have an AI-specific regulatory regime,” Patto said.

“The government has been clear that existing laws will do the heavy lifting – in practice, that’s mainly privacy law, alongside consumer and discrimination.”

Patto explained privacy law “focuses on purpose”, while explicit consent is only required “in a relatively narrow set of situations”.

“Using Gmail’s AI Inbox as an example, it’s important to be clear about what’s happening.

“This isn’t Google using emails for Google’s own purposes, it’s the mailbox owner choosing to enable a feature to help manage their own inbox.

“The primary compliance question is therefore whether the organisation turning the tool on can lawfully use it in that way, rather than whether Google is secretly exploiting people’s emails.”

Indeed, Patto compared the tool to spam filtering, noting senders aren’t expected to give explicit consent “every time a recipient’s inbox scans an email for security or inbox management”.

“Where consent becomes much more relevant is where email content is used for something materially different, such as training or improving models,” said Patto.

“For an email-summary tool that isn’t training on content and isn’t repurposing messages for other uses, it’s difficult to argue that explicit consent from every sender is legally required as a general rule.”

Patto expects these kinds of features will ultimately “become the norm”, while what counts as a “reasonable expectation” under privacy law will evolve over time.

As the technology grows more common, McKay noted it was particularly concerning that the US, where many of these technologies are being developed, has “no single privacy law”.

“Meanwhile, China has very different cultural conceptions of privacy based on an underlying collectivist culture, where the family unit is the basic unit instead of the individual.

“For those of us somewhere like Australia, it means our assumptions, legal and cultural, will not be baked in.”