The federal government will consider backflipping on a special exemption it handed YouTube from the social media age ban after the eSafety Commissioner labelled it “inconsistent”.

eSafety Commissioner Julie Inman Grant has handed Communications Minister Anika Wells a 16-page report based on a survey of 2,600 children who will be impacted by the social media ban for under 16-year-olds, which was passed by Parliament late last year and will come into effect in December.

The law will require certain social media platforms to take “reasonable steps” to prevent under 16s from holding accounts, or face fines of up to $50 million.

In the report, Inman Grant said YouTube is the social media platform where children are most likely to see harmful content and urged the government to not exempt it from the age ban.

“Given the known risks of harm on YouTube, the similarity of its functionality to the other online services, and without sufficient evidence demonstrating that YouTube predominantly provides beneficial experiences for children under 16, providing a specific carve-out for YouTube appears to be inconsistent with the purpose of the Act,” the eSafety Commission report states.

A spokesperson for Wells said she will consider the recommendation, while the Australian Financial Review cited government sources who said the Department will agree to remove the exemption.

The spokesperson for the Minister said no decision has been made yet, and that she is “carefully considering” the advice.

“The Minister’s top priority is making sure the draft rules fulfil the objective of the Act – protecting children from the harms of social media,” the spokesperson told Information Age.

A controversial exemption

The federal government had been planning to exempt YouTube from the age ban due to its use for educational purposes.

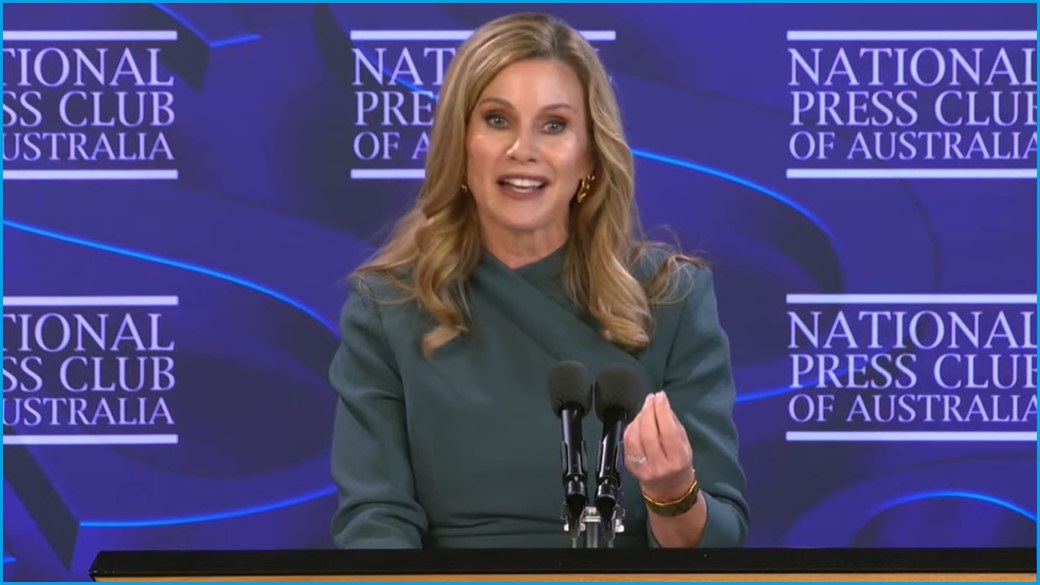

Inman Grant also addressed the National Press Club on Tuesday afternoon and expanded on why she thinks YouTube should be included in the scheme.

“The New York Times reported earlier this month that YouTube surreptitiously rolled back its content moderation processes to keep more harmful content on its platform, even when the content violates the company’s own policies,” she said in the speech.

“This really underscores the challenges of evaluating a platform’s relative safety at a single point in time, particularly as we see platform after platform winding back their trust and safety teams and weakening policies designed to minimise harm, making these platforms ever-more perilous for our children.”

YouTube quickly hit back at the recommendation, saying that it was “inconsistent and contradictory”.

“We urge the government to follow through on the public commitment it made to ensure young Australians can continue to access enriching content on YouTube,” YouTube Australia public policy and government relations senior manager Rachel Lord said in a statement.

YouTube pointed to a survey last year that found 84 per cent of teachers use YouTube at least monthly in the classroom.

The company also denied that it had made any changes to its policies that had negatively impacted younger users.

Many of the social media giants covered by the ban, including Meta, TikTok and Snap, also criticised YouTube’s exemption.

In a statement and submission to the federal government, TikTok said the exemption was “irrational”, “shortsighted” and a “sweetheart deal”.

Meta said there had been a “disregard of evidence and transparency in how the government is determining which services will be included under the law”.

But the eSafety Commission research found that among surveyed children who had seen or heard potentially harmful content online, nearly 40 per cent reported their most recent or impactful experience of this occurred while on YouTube.

Harmful content rife online for children

For the report, harmful content was described as misogynistic or hateful material, dangerous online challenges, violent fight videos and posts promoting disordered eating.

It found that 96 per cent of children aged between 10 and 16 had used at least one social media platform, and 70 per cent had encountered harmful content.

One in seven of the children surveyed had experienced grooming-like behaviour from adults or other children at least four years older than them online.

The federal government also released research on consumer sentiments about the ban based on a survey of more than 3,000 adults and 800 children that it received nearly six months earlier.

The research found “significant trust and security concerns” among some of these surveyed.

The trial of age assurance technologies that may be used by the social media companies to enforce the ban delivered mixed results, with no single technology solution working in all situations.

More than 50 companies offered up their technology for the testing, with some producing “scarily accurate” results, others experiencing issues, and some keeping too much data.